Welcome to

GRIFFIN GLOSSARY

“Your clear, trusted guide to green finance and sustainability jargon”

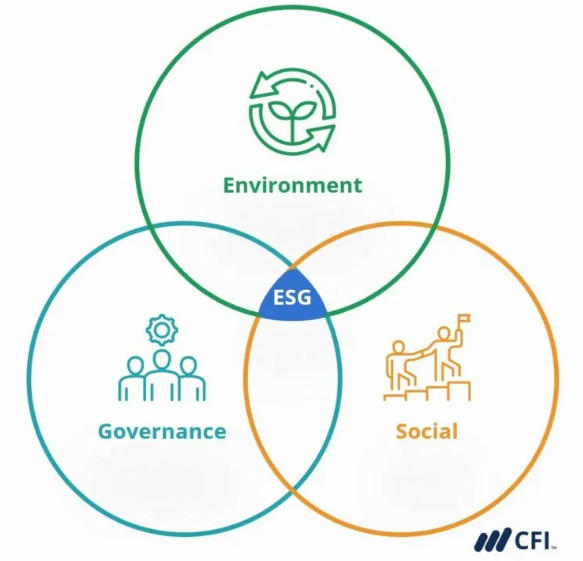

ESG

ESG stands for Environmental, Social, and Governance.

It’s a set of standards investors use to evaluate how a company operates sustainably and ethically. The Environmental aspect considers how a company safeguards nature, from carbon emissions to waste management.

The Social part looks at how a company manages relationships with employees, suppliers, and communities. Governance examines a company’s leadership, audits, internal controls, and shareholder rights.

Together, ESG factors help investors spot risks and opportunities not visible in financial statements alone. Strong ESG performance often indicates responsible management and long-term stability.

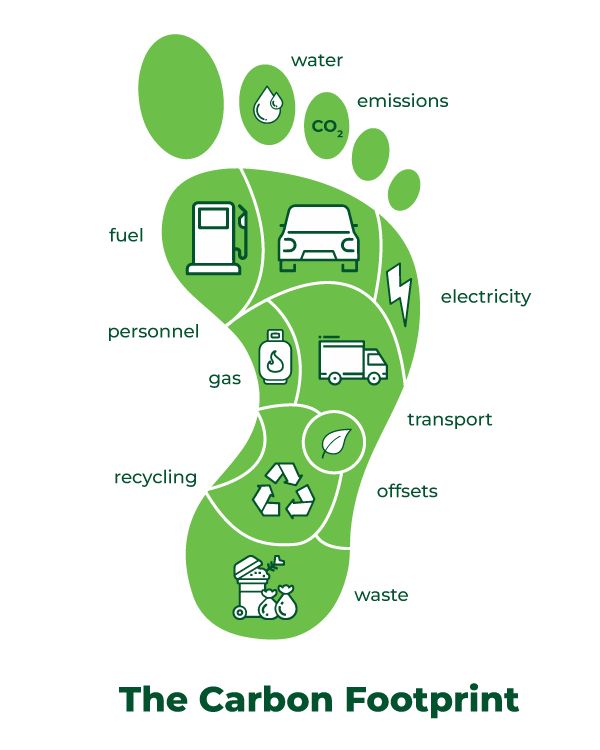

Carbon Footprint

A carbon footprint measures the total greenhouse gas emissions caused directly or indirectly by an individual, organization, or product.

It is usually measured in tonnes of CO₂ equivalent (CO₂e) per year.

This includes everything from energy used to manufacture a product to fuel burned while transporting it.

Understanding your carbon footprint helps you identify where you can cut emissions.

Companies calculate it to comply with climate targets and show accountability.

Reducing footprints can involve using renewable energy, improving efficiency, or offsetting emissions.

It’s a key step toward climate action for both businesses and individuals.

Green Bond

Green bonds are a type of fixed-income financial instrument.

They are used to raise capital exclusively for environmentally friendly projects.

Common projects include renewable energy plants, clean transportation, and sustainable water management.

Governments, banks, and corporations issue green bonds to attract eco-conscious investors.

These bonds follow principles like the Green Bond Principles for transparency. They help direct large amounts of private capital towards climate solutions. As demand grows, green bonds play a big role in financing a greener economy.

Net Zero

Net zero means achieving a balance between greenhouse gases emitted and those removed from the atmosphere.

To reach net zero, an organization must cut emissions as much as possible.

Any remaining emissions are offset by actions like planting trees or using carbon capture. The goal is to stop adding to global warming and stabilize climate impacts.

Countries and companies worldwide set net zero targets for 2030, 2040, or 2050.

Achieving net zero involves changing energy use, supply chains, and even customer behaviors.

It’s a cornerstone of the Paris Agreement and vital for limiting global temperature rise.

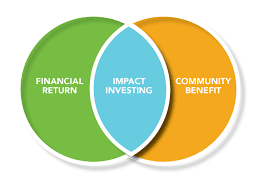

Impact Investing

Impact investing refers to investments made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside financial returns.

Unlike traditional investing, it focuses on doing good while making money.

Popular areas include affordable housing, renewable energy, healthcare, and education. Impact investors monitor and report the outcomes their money achieves.

Foundations, development banks, and even pension funds engage in impact investing.

It aligns capital with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The market is rapidly growing as more investors demand purpose-driven portfolios.

Circular Economy

The Circular Economy is a model focused on minimizing waste and making the most of resources.

It contrasts with the traditional linear model of “take, make, dispose.”

Products and materials are designed to be reused, repaired, or recycled in closed loops. It promotes business models like product-as-a-service, resale, and regenerative design.

Reducing raw material use lowers emissions and builds supply chain resilience. Circular practices reduce landfill waste and dependence on finite resources.

It offers both environmental benefits and cost savings over time.

Greenwashing

Greenwashing is when a company falsely presents its products, practices, or image as environmentally responsible.

It can involve misleading marketing, vague claims like “eco-friendly,” or exaggerating small sustainability efforts.

The goal is often to attract conscious consumers or investors without genuine change.

Greenwashing damages trust and makes it harder to identify truly sustainable businesses. Regulators are increasingly cracking down through advertising standards and reporting rules.

Investors now demand verifiable ESG data to avoid greenwashed assets. Recognizing and avoiding greenwashing is key to informed ethical decision-making.

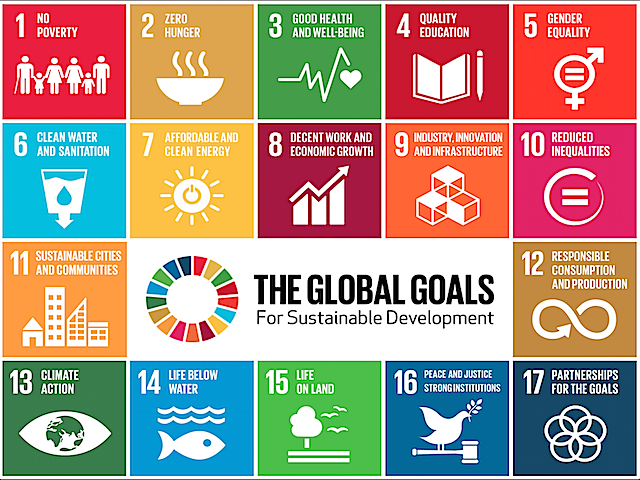

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The SDGs are 17 global goals adopted by the UN in 2015 to address urgent social, economic, and environmental challenges.

They include goals like zero hunger, clean energy, gender equality, and climate action.

Each SDG has specific targets to be achieved by 2030.

Governments, businesses, and civil society use them as a roadmap for sustainability.

Investors often align impact strategies and disclosures with the SDGs. They encourage systemic thinking and cross-sector collaboration.

The SDGs provide a shared language and direction for building a better world.

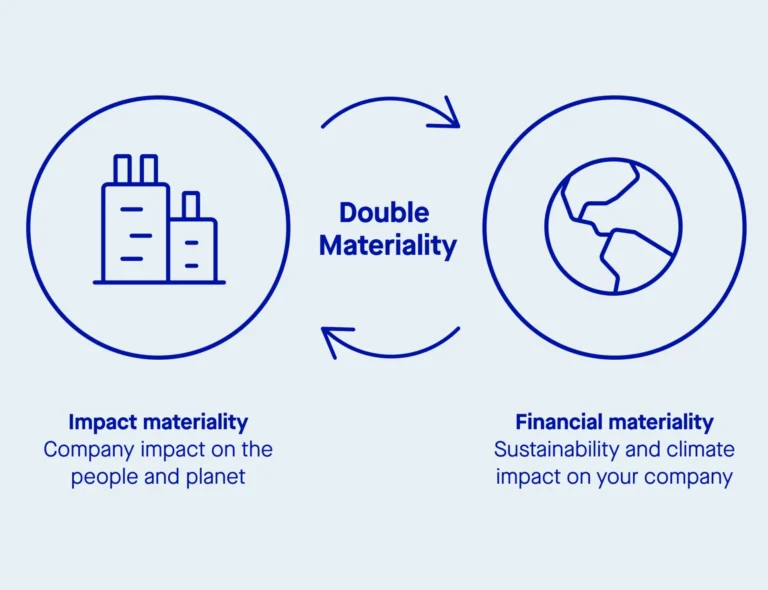

Double Materiality

Double Materiality means considering how sustainability issues impact both a company’s performance and the world around it.

It expands the traditional view of materiality beyond investor risks. For example, climate change may affect a business financially, but the business also impacts climate.

This concept is central to EU sustainability reporting standards and frameworks like CSRD.

It encourages companies to disclose both financial and societal consequences of their actions. Double materiality helps investors and stakeholders understand broader risks and responsibilities. It promotes more transparent and accountable sustainability reporting.

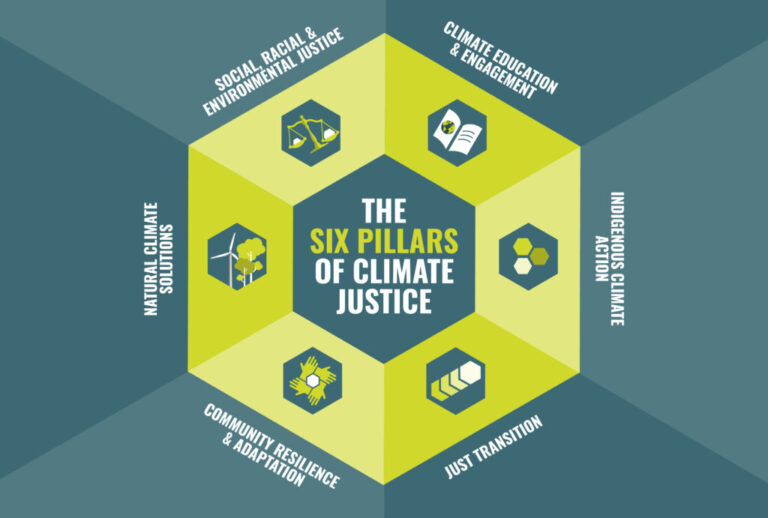

Just Transition

A Just Transition ensures that the shift to a green economy is fair and inclusive for all workers and communities.

It addresses potential job losses in fossil fuel industries through reskilling, support, and social protection. The concept recognizes that climate action must also be socially just.

Governments and unions often use it in climate policy planning. It includes empowering marginalized groups and promoting decent green jobs.Investors are increasingly assessing companies on their Just Transition strategies.

It bridges environmental progress with equity and human dignity.

Transition Risk

Transition Risk refers to financial risks arising from the shift toward a low-carbon economy.

This includes policy changes, new regulations, carbon pricing, and market preferences shifting. Companies reliant on fossil fuels or outdated technologies may face asset stranding or devaluation. Transition risk affects creditworthiness, insurance costs, and investment attractiveness.

Forward-looking firms adapt by innovating and disclosing their transition plans. It’s one of the key components of climate-related financial risk, alongside physical risks.

Managing transition risk is essential for long-term business resilience and investor confidence.

Biodiversity Loss

Biodiversity loss refers to the decline in the variety of life on Earth, ranging from ecosystems to species and genes.

It threatens food security, clean water, disease regulation, and climate resilience.

Key drivers include deforestation, pollution, habitat destruction, overexploitation, and climate change. Businesses that depend on natural resources or supply chains face risks from biodiversity decline.

Emerging frameworks like TNFD aim to integrate biodiversity into financial decision-making.

Preserving biodiversity is vital for sustainable development and long-term value creation.

Carbon Pricing

Carbon pricing assigns a cost to emitting carbon dioxide, encouraging polluters to reduce their emissions.

There are two main approaches: carbon taxes (a set price per ton) and cap-and-trade systems (market-based limits).

It helps internalize the environmental cost of carbon, making pollution economically visible. By raising the cost of high-carbon activities, carbon pricing drives innovation and clean alternatives. Many countries, regions, and even private firms now use carbon pricing in their strategies.

Investors track carbon price exposure as part of transition risk and climate scenario analysis. It’s a key policy tool in reaching global decarbonization goals.

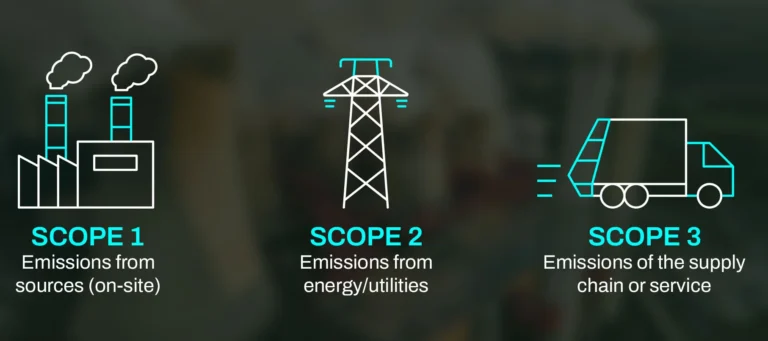

Scope 1, 2, and 3 Emissions

These are categories used to classify a company’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Scope 1 covers direct emissions from owned or controlled sources, such as company vehicles or factories.

Scope 2 includes indirect emissions from the generation of purchased electricity, steam, heating, and cooling.

Scope 3 encompasses all other indirect emissions in a company’s value chain, like business travel, waste disposal, and supplier emissions.

Understanding these scopes helps companies and investors in creating targeted and transparent decarbonization strategies. Together, they provide a complete emissions profile for climate action planning.

Decarbonization

Decarbonization refers to the process of reducing or eliminating carbon dioxide emissions from a system or economy.

It’s most commonly achieved by shifting to renewable energy sources, improving energy efficiency, and electrifying transportation. Governments, investors, and businesses all play key roles via policy reform, green innovation, and carbon pricing mechanisms. It’s a foundational step for reaching net-zero emissions and meeting global climate targets.

Companies that lead in decarbonization often gain competitive advantages as economies transition to low-carbon models.

Green Taxonomy

A green taxonomy is a classification system that defines what economic activities are environmentally sustainable.

It helps guide public and private investment toward green initiatives like renewable energy and sustainable agriculture.

The EU Taxonomy is the most well-known framework and sets the tone globally for green finance alignment.

Such taxonomies improve market transparency, prevent greenwashing, and foster confidence in ESG-linked products.

Emerging economies are also developing local taxonomies to attract sustainable finance aligned with national priorities.

Climate Risk Disclosure

Climate risk disclosure is the act of reporting how climate-related risks may affect a company’s operations, assets, and long-term outlook.

Disclosures include both physical risks (like flooding or heatwaves) and transition risks (like regulatory changes or market shifts). Frameworks like the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) standardize how this information is shared.

Companies with strong disclosures are better prepared for climate disruptions and more attractive to responsible investors. Effective disclosures also support stakeholder trust and enhance strategic decision-making.

Science-Based Targets (SBTs)

Science-Based Targets are corporate climate goals aligned with the emissions reductions needed to limit global warming.

They are validated by the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) to ensure scientific credibility. SBTs drive companies to set emissions pathways that meet 1.5°C or 2°C climate scenarios. They help businesses future-proof operations, meet regulatory expectations, and build investor confidence.

Adopting SBTs can also uncover inefficiencies and drive innovation in supply chains and operations. These targets have become a key metric in ESG investing and corporate sustainability leadership.

Environmental Justice

Environmental justice is the principle that all people deserve equal protection from environmental harm.

It addresses systemic inequalities where low-income and marginalized communities bear a disproportionate share of pollution and climate risks.

Policies rooted in environmental justice aim to provide equitable access to clean air, water, and green spaces.

It’s also about empowering communities to participate in decisions affecting their environment and health.

Many global initiatives now embed environmental justice as a core criterion for funding and regulation as it is integral to inclusive climate solutions.

Stranded Assets

Stranded assets are investments that may lose value due to external forces like regulation, market shifts, or environmental concerns.

These include fossil fuel reserves, aging coal plants, and other high-carbon infrastructure.

As climate policies tighten and technologies evolve, such assets may become unusable or economically obsolete.

Investors are increasingly evaluating exposure to stranded assets in their portfolios. Managing this risk is essential for long-term financial resilience and transition planning.

Understanding which assets are vulnerable enables better capital allocation and strategic divestment.

Sustainable Development

Sustainable development is a model of progress that meets today’s needs without compromising future generations.

It harmonizes economic growth, environmental stewardship, and social well-being.

The United Nations’ 17 (SDGs) offer a global blueprint for sustainable prosperity. Governments, businesses, and civil society are all key actors in advancing this agenda.

It promotes responsible use of natural resources, inclusive economic policies, and climate resilience.

Sustainable development is central to ESG investing and long-term value creation.

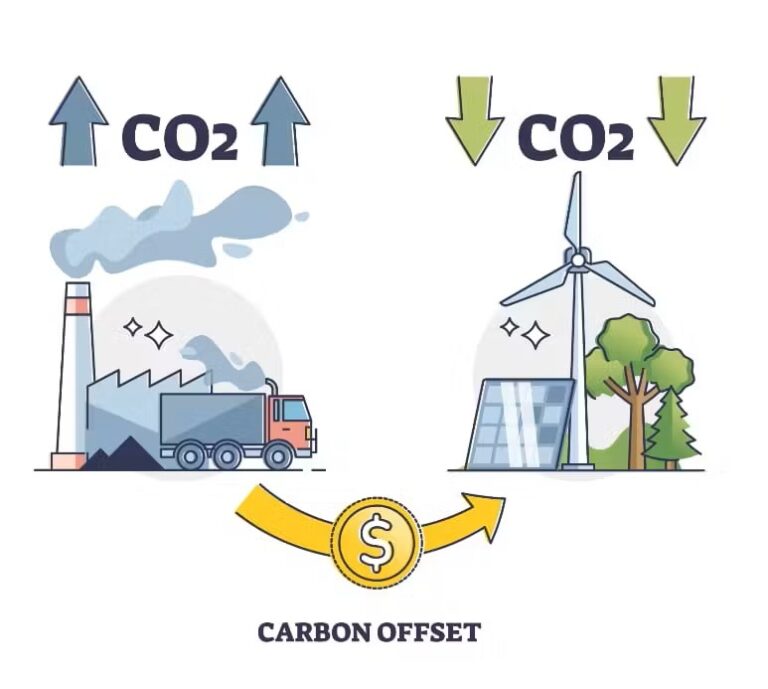

Carbon Offset

A carbon offset represents a verified reduction of carbon emissions made to compensate for emissions produced elsewhere.

Common offset projects include reforestation, renewable energy, and methane capture. Offsets are used by individuals, companies, and governments to meet net-zero goals or offset difficult-to-eliminate emissions.

For effectiveness, offsets must be additional, permanent, and third-party verified. They are a flexible tool but not a substitute for direct emissions cuts.

The voluntary carbon market helps channel funds toward climate-positive initiatives through offsets.

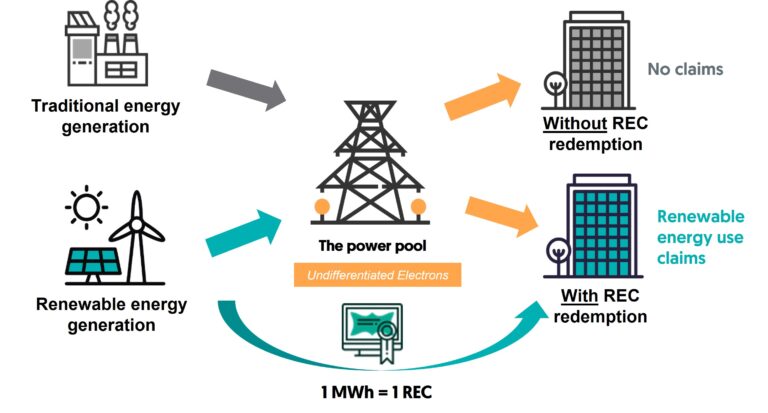

Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs)

RECs are market instruments that certify electricity has been generated from renewable sources.

Each certificate represents 1 megawatt-hour (MWh) of clean energy added to the grid.

Organizations purchase RECs to claim renewable energy usage and reduce their Scope 2 emissions.

They support renewable project development and provide traceability in corporate sustainability efforts.

RECs are often used in carbon accounting, ESG reporting, and green marketing claims.

While not physical power, they symbolically shift demand from fossil fuels to clean energy.

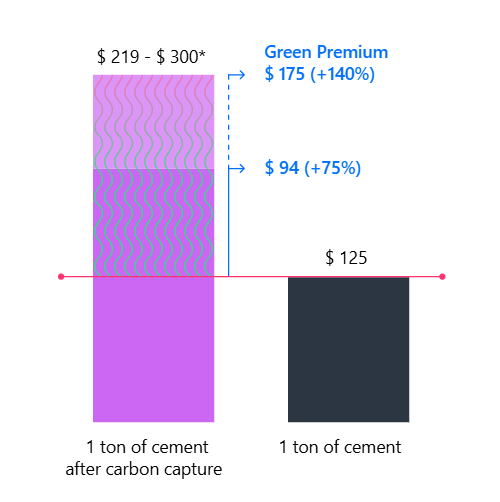

Green Premium

The green premium is the extra cost of choosing a sustainable product or solution over its conventional counterpart.

It applies to technologies like electric vehicles, clean steel, or plant-based packaging. The premium exists due to higher production costs, limited supply chains, or emerging innovation.

Reducing this premium is key to mainstreaming green alternatives and scaling sustainability. Policy incentives, subsidies, and corporate demand can help lower these costs. Understanding the green premium allows businesses and consumers to make informed trade-offs.

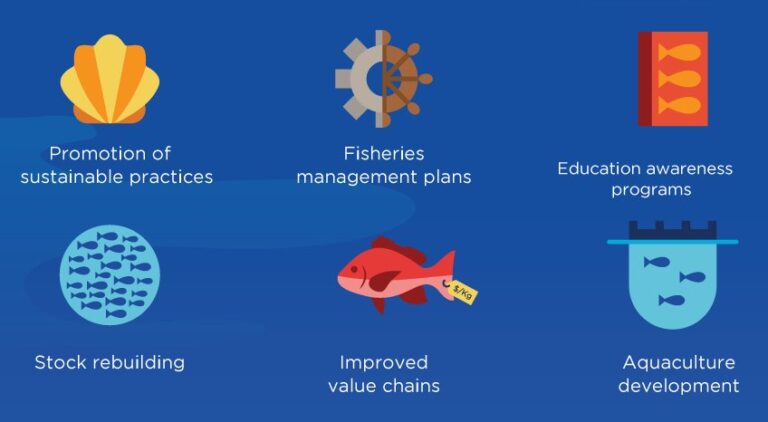

Blue Bonds

Blue bonds are financial instruments specifically aimed at ocean conservation and sustainable water use.

They’re similar to green bonds but focus on marine ecosystems, fisheries, and coastal protection.

Issued by governments or development banks, they attract investors looking for environmental returns.

Funds may support coral reef restoration, sustainable fishing, or water pollution control.

Blue bonds raise awareness of water as a vital and finite resource. They’re gaining traction as part of the broader sustainable finance toolkit. These bonds support both biodiversity and economic livelihoods tied to oceans.